At mid-century, drugs went through testing before landing on the market. The government also split them into over the counter (OTC) drugs and prescription drugs. While ad campaigns focused on selling OTC brands to consumers using new techniques and tactics pioneered in the “Mad-Men Era” of marketing, ads for prescription drugs focused solely on doctors. Americans would be unfamiliar with prescription drugs options because they seldom if ever saw ads for prescription drugs.

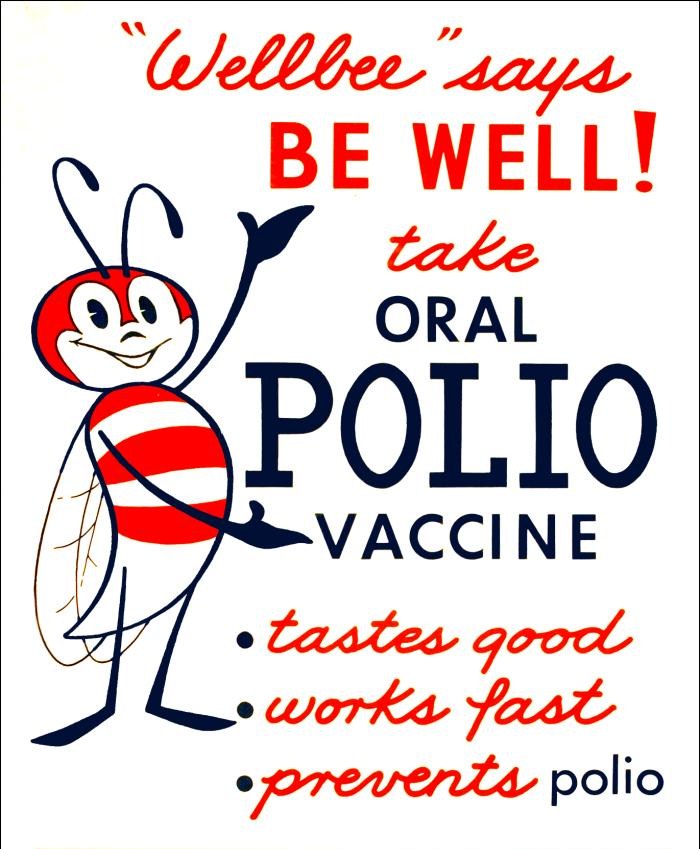

After the Second World War, the US entered the prime years of the so-called “Golden Age of Medicine.” Trust in institutions including the medical establishment reached their historical maximums. The medical men and women now operated with the magic bullets like penicillin, insulin, and the polio vaccine. FDR sold Americans on four freedoms during World War II (freedom from want and fear, freedoms of worship and speech), and now medicine seemed to promise freedom from illness. The science behind all of this, caught between the technical triumphs of the atom bomb and space race, seemed to hold limitless promise.

Science and medicine’s supreme technical authority reversed the past century’s trend of consumerist medicine. Doctors and drug companies made consumers into patients. Care was something done for them and the deeply ingrained American belief in the right to self-treat, so prevalent in 1900, disappeared.

But consumerism and health care would not stay apart forever, nor would advertising to patients be contained indefinitely.

Setting the Stage for Overhaul

At no point in the 1950s or 60s had the FDA specifically forbidden advertising prescription drugs to patients. Rather, that decision had been made by manufacturers who did not see value in advertising beyond physicians. This caution increased as the use of thalidomide caused severe birth defects in Europe and the public awakened to the repercussions of chemical compounds like DDT and penicillin allergies. In 1962, Congress passed a series of amendments to Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that expanded the FDA’s authority to ensure that prescription drugs were not just safe but effective before being sold in the US. It also dramatically expanded labelling requirements, including displaying risks, ingredients, and usage (for OTC drugs) in plain language.

In 1969, the FDA adopted additional measures that would govern future pharmaceutical advertising. These regulations stipulated that drug ads would have to be fair and balanced by disclosing potential adverse effects as well as therapeutic value. They also required package labelling information to accompany broadcast presentations, including information related to side effects. The “adequate provision” clause created a level of uncertainty among broadcast advertisers, but the prevailing thought process through the 1970s continued to be that the real gatekeepers for prescription medicine were those writing the prescription.

While advertising’s thinking stayed somewhat the same, the relationship between patients and healthcare providers began to change. After 1965 and the launch of Medicare, early forms of patient-centered care began to position patients as co-creators of their treatments. Ideas like informed consent (introduced in 1957, emerged in public discourse in 1971) underscored the importance of apprising patients of their journeys. Historians often point to this period as the end of the “Golden Age of Medicine,” the dissolution of lightly questioned medical authority. Its end and the growing important of the patient in their own treatment probably stem from deteriorating trust in institutions and authority’s characteristic of the Vietnam era. With patients in the passenger seat, physicians began to re-imagine ways to communicate treatment to patients. These communication strategies, which now birthed the idea of discussing “treatment options,” helped pave the way for branding in American medicine years later. The return of consumer choice opened the options for brands to compete.

The demand on the healthcare system and revolution in consumer rights in the 70s also ushered in Patient Packaging Inserts (PPI). Consumer advocates believed that the quickening pace of medicine (and the growing distrust of physicians and hospitals) limited the prescriber’s ability to communicate information about medicine safely and clearly. These inserts accompanied about 10 different classes of drugs in their early days and informed patients how to effectively administer the drugs as well as warning about their potential adverse effects. PPIs are perhaps most important in the story of advertising two ways: first, consumer advocates and physicians who supported PPIs identified a lack of trust in physicians to accurately communicate medical information on side effects. Second, PPIs reaffirmed that patients could indeed understand the risks of drugs if they had adequate, plain language explanations.

That patients could both consume medical information and wanted education marked a shift in the assumptions of American medicine. Instead of going to the doctor to get well, patients now claimed a desire to understand why doctors recommended a particular approach. Unsurprisingly, what we would recognize today as unbranded awareness campaigns followed PPIs in the late 70s and early 80s. Companies like Pfizer and Eli Lilly began promotions to make the public aware of underdiagnosed lifestyle diseases like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and osteoarthritis.

But then came Boots, who launched a print and broadcast media campaign around Rufen, it’s then prescription only ibuprofen drug. (Merck subsequently launched a branded vaccine campaign soon after). The transition to branded campaigns caused alarm and panic in Washington. Could the public make sense of the information provided in a short ad? Would it undermine the authority of physicians? How could they find reliable information to understand the risks and benefits of a particular drug?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers also hotly debated the way forward. Some companies believed that brand-specific marketing would lead to an escalation in costs at a time when pipelines, discovery, and approval moved at a snail’s pace compared to today. Others, however, pointed to university-sponsored research showing patients wanted a greater understanding of prescription drugs. In the days before the internet, advertisements placed information at the general publics’ fingertips, and print and television ads represented a key educational tool.

Finally, a third presence now penetrated exam rooms across the country: for profit insurance providers. First greenlit to operate as for profit in 1973, insurance companies sought to control costs to increase profits. The Blue Cross and Blue Shield networks, the last major non-profit in the insurance game, suffered catastrophic losses throughout the 80s and early 90s. Costs had to be controlled to simply survive. (BCBS would transition to for profit in 1993).

A new mindset slowly emerged among manufacturers. Not only could physicians insulate patients from their newest treatments as had always been the case, but insurance represented an additional and more adversarial barrier to the viability of new drugs. Urgency was added as many of the 1970s and 1980s best-selling prescription drugs (ibuprofen in 1984 for instance), would soon generate less cash as they moved to the OTC category.

The needle had shifted toward an environment that we might recognize today, but it would take a major health crisis (HIV/AIDS) and the resulting federal action to truly create the DTC advertising we see today.

Leave a comment