It might not be awe inspiring or particularly striking, but these 22 seconds marked a paradigm shift in the history of American medicine. Broadcast for just a few days before the FDA suspended it from the air waves, the Boots Rufen Campaign set the stage for the direct to consumer (DTC) environment of pharmaceutical advertisements today. Forty years later, pharma makes up a nearly $6 billion dollar part of the advertising industry — and splits public opinion over whether DTC ads empower consumer decisions or raise costs to consumers.

So how did we get here? Did our grandparents contend with pharma ads? And how did people make sense of the medical information provided to them in the days before the internet?

Let’s take a look back at the evolution of drug advertisements over the last 150 years …

Patent Medicine

In the late 1800s, most Americans had access to three kinds of “medicine.” First were home remedies normally appearing in cookbooks or passed down within families or communities. This might be castor oil to induce vomiting or cool wash clothes for fever. Maybe even putting butter on burns (don’t do this, it makes them way worse). They had varying efficacy, but since calling the doctor could be an immense financial burden, they formed a core of treatment in every American household.

Second would be medicines prescribed by doctors and prepared by pharmacologists or apothecaries. These treatments mostly came from a standardized set in the United State Pharmacopeia, first published in 1820. It’s easiest to conceptualize the nineteenth century tome as a database of record, recipe book, encyclopedia, and reference guide carefully wrapped in one. Most recipes have no clinical efficacy in the modern sense, but a few contained ingredients that have later shown clinical efficacy. Willow bark for example could be prepared as a pain reliever or fever reducer thanks to the presence of salicylic acid, the active ingredient in aspirin today.

The last form of medicine were patent or proprietary medicines. Private business owners formulated these elixirs, salves, panaceas, or nostrums with a secret blend of ingredients with dubious clinical value to patients. They then made often wild claims about their usage and efficacy. There was no enforced limit on most of these medications. Some contained opiates, mercury, or other compounds that could harm, kill, or addict their users. Opiate appears often among the list of ingredients. Often the limits between food, drinks, and drugs intermingled. Many used morphine or heroin. Coca-Cola, for example, began life as a remedy. So too did Angostura Bitters, the star of the Manhattan cocktail. And infamously, we derive the term “snake oil” from one of the more odious iterations of these medicines.

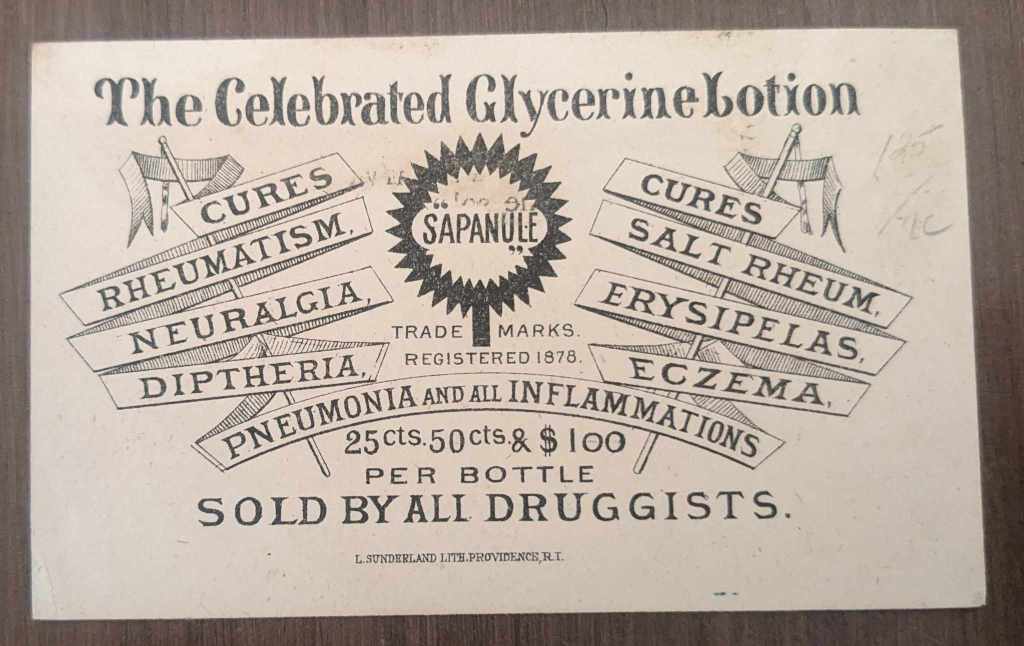

The sheer number of patent medications meant standing out amongst the competition could be challenging, and many patent medicine men ran early forms of marketing and sales campaigns. Many employed salesmen to talk in the street or go door-to-door to discuss medicines. Travelling medical shows became features of the Old West and rural south. Some patent medicines painted ads onto the sies of buildings. And at archives across the country, you can still find small, lithographed cards called trade cards. These cards are about the size of a business card and list a concoction’s name, a catchy slogan, and some brightly colored image (often with little pertinence to the ailment they claimed to cure) featured prominently on them. Some feature endorsements by doctors. Others touted a low price, and still others claim to cure specific diseases (one even claimed all diseases).

Some, like the above trade card for glycerin lotion, contain ingredients used in moisturizers today, even if they aren’t used to treat rheumatism or diphtheria.

The proliferation of these cures and remedies created issues for ordinary everyday Americans. Without their ingredients being disclosed or chemically tested, the risk of consuming compounds had disastrous potential. Many remedies contained substances as strange as coal tar, mercury, or other heavy metals.

As the new century rolled in, occasional clusters of poisonings or deaths occurred in the wake of patent medicine. These “medicines” also helped continued scourge of morphine and opium addiction, which reached epic proportions at the end of the nineteenth century.

Consumers had no way of knowing whether the product they bought would cure or kill. But that was little consolation when medicine itself in America had not embraced the scientific principles that emerged in Europe in the 1870s and 1880s. Instead, doctors mostly gave comfort, advice, and Americans rolled the dice on the efficacy of their “snake oil.”

Leave a comment